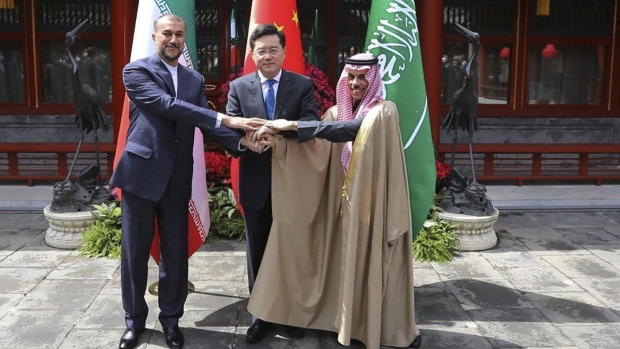

Thursday’s meeting in Beijing between the Saudi and Iranian foreign ministers was a significant step on an unexpected path that may potentially lead to a level of regional stability not seen in over 40 years.That it took place less than a month after the Beijing accord on March 10 is further testimony to Chinese efficiency, and to both parties’ determination to take matters forward.

The two countries were represented on Thursday by their foreign ministers, which suggests that both leaderships are confident about the deal and have now delegated the particulars to the relevant government bodies. This is why it was important that the signing of the initial agreement was attended by Ali Shamkhani, a two-star general and secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, and Mosaed Al-Aiban,

an extremely high-ranking Saudi royal court adviser and one of the crown prince’s most trusted right-hand men. As I understand it this was at the Kingdom’s insistence, and disarmed cynics who said the deal might have been agreed by the Iranian Foreign Ministry but not by Iran’s deep state or its security apparatus; it leaves Tehran no way out by claiming that the deal was not endorsed by everyone in the regime (not that anyone believes there is a genuine separation of powers, but it is an argument that has been used before).

I have been asked many times over the past month how likely it is that the Tehran regime will stick to the deal. Only senior officials in Tehran can answer that. What I do know, as any negotiator will tell you, is that it is true that it doesn’t take much for such a deal to collapse.

Iran’s negotiators are often described as having the patience of Persian carpet weavers. Whether talking with Saudi Arabia or with Western countries, they have always played for time. In the Saudi case, they exploited the fact that all our kings have been of advanced age upon acceding to the throne, so the Iranians knew it was only a matter of time before they had to deal with a new leadership for whom they would not be a priority until they got their house in order.

When dealing with Western democracies, Iran understood that elected leaders changed every few years. Even as recently as the Trump-Biden transition in the White House, all Tehran had to do was survive the former’s maximum pressure campaign until the latter arrived determined to revive the Iran nuclear deal, which meant they could demand concessions.

The good news is that none of this is relevant to the Beijing-sponsored deal that was signed on March 10. What makes that agreement different is that it benefits from the presence of “two-factor authentication” — Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman on the one hand, and China on the other.

The crown prince — young, dynamic and empowered — brings internal stability and foreign policy continuity for decades to come, enabling the relevant officials to focus on every detail of the deal until they see it through. On the other hand, that the agreement was brokered by China and not the US means Tehran cannot wriggle out of it thanks to a Washington administration that may not have bipartisan support in Congress, and in any case will leave after serving its term.

This is also China’s inaugural appearance on the world stage as a peacemaker, and a test of the respect it commands as a global superpower. China has pledged $300 billion of investment in Iran over 25 years and is its biggest trade partner, so there is no doubt that the Chinese dragon will be breathing down Tehran’s neck to ensure that the deal is adhered to — in my view, the only way.

So does this mean that success is guaranteed? Well, in politics it never is. However, there are three possible scenarios.